Read Order: AJWAR v. WASEEM AND ANOTHER [SC- CRIMINAL APPEAL NO. 2639 of 2024]

Tulip Kanth

New Delhi, May 21, 2024: While observing that all the accused-respondents had remained in custody for less than three years for a serious offence of double murder, the Supreme Court has quashed the bail orders passed in their favour by the Allahabad High Court.

The incident in question had taken place on May 19, 2020 in the evening when the appellant-complainant, his two sons, Abdul Khaliq and Abdul Majid with some other persons were sitting in the baithak of his house for breaking the fast (Roza Iftar) and preparing to offer prayers. The accused persons (10 in number, namely, Nazim, Abubakar, Waseem, Aslam, Gayyur, Nadeem, Hamid, Akram, Qadir and Danish) arrived at the spot and indiscriminately fired at the appellant and his two sons. Both the sons of the appellant died on the spot and his nephew, Asjad was seriously injured. The appellant-complainant had alleged that there was previous enmity between the parties due to which the accused persons had attacked him and his sons.

Pertinently, Niyaz Ahmed, father of Waseem (accused No. 7) was not named in the FIR. His role in the incident came up during the course of the investigation conducted by the police and based thereon, his name was added as a co-accused. On completion of the investigation, a chargesheet was submitted under Section 173 Cr.P.C. against eight accused including Abubakar (accused No. 1), Niyaz Ahmad, Aslam (accused No.2) and Nazim (accused No. 8).

The appeals before the Top Court were filed against four different orders of the Single Judges of the Allahabad High Court on applications moved by Waseem (accused No. 7), Nazim (accused No. 8), Aslam (accused No. 2) and Abubakar (accused No.1) in the case registered under Sections 147, 148, 149, 302, 307, 352 and 504 read with Section 34 of Indian Penal Code, 1860 (IPC). The applications filed by them were allowed by different Benches of the High Court. Aggrieved by the said orders, the appellant-Complainant approached the Top Court.

At the outset, The Division Bench of Justice Hima Kohli and Justice Ahsanuddin Amanullah took note of the fact that this was the third time that the appellant-complainant had approached the Top Court for relief. Referring to the post-mortem report, the Bench observed that the deceased, Abdul Khaliq had received one firearm injury in his head and the cause of his death was cranio- cerebral damage as a result of ante-mortem firearm injury which was sufficient to cause death in ordinary course of nature. The post mortem report of the deceased, Abdul Majid showed that he had sustained one firearm entry wound in the abdomen and one exit wound corresponding to each other and the cause of his death was shock and hemorrhage as a result of ante-mortem firearm injury. The injury report of the injured, Asjad (nephew of the appellant-complaint) showed that he had sustained a lacerated wound on the skull and bruises and abrasion on other parts of his body. It was also noticed that so far the deposition of four eye-witnesses had been recorded (PW 1, 2, 3 and 4) and all of them had attributed a role to the accused respondents.

The Bench also set out certain parameters for granting bail. It observed that while considering as to whether bail ought to be granted in a matter involving a serious criminal offence, the Court must consider relevant factors like the nature of the accusations made against the accused, the manner in which the crime is alleged to have been committed, the gravity of the offence, the role attributed to the accused, the criminal antecedents of the accused, the probability of tampering of the witnesses and repeating the offence, if the accused are released on bail, the likelihood of the accused being unavailable in the event bail is granted, the possibility of obstructing the proceedings and evading the courts of justice and the overall desirability of releasing the accused on bail.

“It is equally well settled that bail once granted, ought not to be cancelled in a mechanical manner. However, an unreasoned or perverse order of bail is always open to interference by the superior Court”, it held.

The Bench also explained that if there are serious allegations against the accused, even if he has not misused the bail granted to him, such an order can be cancelled by the same Court that has granted the bail. Bail can also be revoked by a superior Court if it transpires that the courts below have ignored the relevant material available on record or not looked into the gravity of the offence or the impact on the society resulting in such an order.

The Bench further added that the considerations that weigh with the appellate Court for setting aside the bail order on an application being moved by the aggrieved party include any supervening circumstances that may have occurred after granting relief to the accused, the conduct of the accused while on bail, any attempt on the part of the accused to procrastinate, resulting in delaying the trial, any instance of threats being extended to the witnesses while on bail, any attempt on the part of the accused to tamper with the evidence in any manner.The Bench also made it clear that this list is only illustrative and not exhaustive. However, the court must be cautious that at the stage of granting bail, only a prima facie case needs to be examined and detailed reasons relating to the merits of the case that may cause prejudice to the accused, ought to be avoided. The bail order should reveal the factors that have been considered by the Court for granting relief to the accused. Reference was also made to the judgments in Puran v. Ram Bilas and Another [LQ/SC/2001/1208] ; Narendra K. Amin (Dr.) v. State of Gujarat and Another [LQ/SC/2008/991].

Coming to the facts of the case, the Bench opined that the High Court had completely lost sight of the principles that conventionally govern a Courts discretion at the time of deciding whether bail ought to be granted or not. The High Court has ignored the fact that the appellant-complainant had stuck to his version as recorded in the FIR and that even after entering the witness-box, the appellant-complainant and three eyewitnesses had specified the roles of the accused- respondents in the entire incident.

The High Court also overlooked the fact that the respondents have previous criminal history details whereof have been furnished by the Counsel for the State of UP. The accused Nazim was granted bail in 2017 and while on bail, he was alleged to have committed a double murder of the two sons of the appellant-complainant. Moreover, while on bail, there had been allegations that three of the accused- respondents herein had threatened one of the key eye-witnesses, Abdullah (PW-2) in open Court, thrashed him and threatened to kill him in the Court premises. The attempt to delay the trial on the part of the respondents has also surfaced from the records.

Most importantly, the High Court had overlooked the period of custody of the respondents-accused for such a grave offence alleged to have been committed by them. All the accused-respondents had remained in custody for less than three years for such a serious offence of a double murder for which they have been charged.

All these factors when examined collectively, left no manner of doubt that the respondents did not deserve the concession of bail. Thus, the Top Court quashed all the four impugned orders and directed the respondents to surrender within two weeks.

Read Order: Dani Wooltex Corporation & Ors v. Sheil Properties Pvt. Ltd. & Anr [SC- CIVIL APPEAL NO. 6462 OF 2024]

LE Correspondent

New Delhi, May 21, 2024: The Supreme Court has explained that mere absence in proceedings or failure to participate does not, per se, amount to abandonment and the Arbitral Tribunal can take recourse to Section 25 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996 in order to continue with or terminate the proceedings if the parties remain absent.

The Division Bench of Justice Abhay S. Oka & Justice Pankaj Mithal was considering the issue about the legality and validity of the order of termination of the arbitral proceedings under clause (c) of sub-section (2) of Section 32 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996 (Arbitration Act) passed by the Arbitral Tribunal.

The first appellant, Dani Wooltex Corporation, is a partnership firm that owned certain land in Mumbai. The first respondent, Sheil Properties (Sheil), a private limited company, was engaged in real estate development. The second respondent, Marico Industries (Marico), is also a limited company in the consumer goods business. A part of the first appellant's property was permitted to be developed by Sheil under the Development Agreement and a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) was executed by and between the first appellant and Marico, by which the first appellant agreed to sell another portion of its property to Marico. Under the MOU, Marico was given the benefit of a certain quantity of FSI/TDR. Marico issued a public notice inviting objections, to which Sheil submitted an objection and stated that any transaction between the first appellant and Marico would be subject to the Agreement.

The dispute between the first appellant and Sheil led Sheil to institute a suit for the specific performance of the MOU as modified by the alleged consent terms. The first appellant and Marico were parties to the said suit. Marico also filed a suit against the first appellant, and Sheil was also made a party defendant to the suit. The arbitral proceeding based on Maricos claim was heard earlier, culminating in an award.

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the set meeting was held a little later when the Arbitral Tribunal directed the first appellant to file a formal application for dismissal of the claim of Sheil and permitted Sheil to file a reply. Accordingly, the first appellant filed an application invoking the Arbitral Tribunals power under clause (c) of sub-section (2) of Section 32 of the Arbitration Act. The contention raised by the first appellant in the said application was that Sheils conduct of not taking any steps for eight years showed that the said company abandoned the arbitral proceedings. The Arbitral Tribunal passed an order terminating the arbitral proceedings in the exercise of power under Section 32(2)(c) of the Arbitration Act.

Sheil filed an application before the Bombay High Court to challenge the legality and validity of the order of the Arbitral Tribunal by taking recourse to Section 14(2) of the Arbitration Act. By the impugned judgment and order, the Single Judge set aside the order of termination of the proceedings. The appellants disputed this judgment.

Referring to Sections 14 & 15, the Bench held that an Arbitrator always has the option to withdraw for any reason. Therefore, he can withdraw because of the parties' non-cooperation in the proceedings. But in such a case, his mandate will be terminated, not the arbitral proceedings.

Placing reliance upon Sections 25 & 32, the Bench clarified that if a party fails to appear for a hearing after filing a claim, the Arbitrator cannot say that continuing the arbitral proceedings has become unnecessary. Abandonment by the claimant of his claim may be grounds for saying that the arbitral proceedings have become unnecessary. However, the abandonment must be established. Abandonment can be either express or implied. Abandonment cannot be readily inferred.

“Mere absence in proceedings or failure to participate does not, per se, amount to abandonment. Only if the established conduct of a claimant is such that it leads only to one conclusion that the claimant has given up, his/her claim can an inference of abandonment be drawn. Merely because a claimant, after filing his statement of claim, does not move the Arbitral Tribunal to fix a date for the hearing, it cannot be said that the claimant has abandoned his claim. The reason is that the Arbitral Tribunal has a duty to fix a date for a hearing. If the parties remain absent, the Arbitral Tribunal can take recourse to Section 25”, it added.

The Bench also stated, “The failure of the claimant to request the Arbitral Tribunal to fix a date for hearing, per se, is no ground to conclude that the proceedings have become unnecessary.”

Coming to the facts of the case, the Bench observed that there was no abandonment either express or implied. The failure to challenge the award on Marico’s claim would not amount to abandonment of the claim filed by Sheil in January 2012. In the claim submitted by Sheil, a prayer was made in the alternative for passing an award in terms of money against the first appellant.

“Therefore, we hold that there was absolutely no material on record to conclude that Sheil had abandoned its claim or, at least, the claim against the first appellant”, the Bench said while also noting that till the award was passed in Marico’s claim, Sheil’s representative was always present at all hearings till the passing of the award. After the award, the Arbitrator never convened a meeting to deal with Sheil’s claim. Hence, the finding of the Arbitrator that there was abandonment of the claim by the first appellant was held to be not based on any documentary or oral evidence on record. As per the Bench, the Arbitrator committed illegality as such a finding could never have been rendered on the material before the Arbitral Tribunal.

Thus, the Bench concurred with the view of the Single Judge and dismissed the appeal. Noting that the sole Arbitrator had withdrawn from the proceedings, the Bench held that the parties would take necessary steps to get the substituted Arbitrator appointed in accordance with law.

Read Order: SMT. SHYAMO DEVI AND OTHERS v. STATE OF U.P. THROUGH SECRETARY AND OTHERS [ SC- CIVIL APPEAL NO. 5539 OF 2012]

LE Correspondent

New Delhi, May 21, 2024: While upholding the land allotments made under the Uttar Pradesh Zamindari Abolition and Land Reforms Act (UPZALR Act) in the year 1994, the Supreme Court has made it very clear that the Collector has the power to initiate suo moto action for cancellation of allotment under sub-section (6) of Section 122-C in case of fraud. The Top Court reaffirmed that the suo moto power should be exercised within a reasonable period of time.

The factual scenario of this case was such that in the year 1969-70, the khasra plot in Rampur Kedhar Village, UP was designated as a Panchayat Ghar but later it was declared unsuitable in 1993. On the request of the village Pradhan a portion of the said plot was re-assigned for residential use by the Assistant Collector and subsequently different plots of land in said survey number came to be allotted to different individuals including the writ petitioners under Section 122-C(i)(d) of Uttar Pradesh Zamindari Abolition and Land Reforms Act (UPZALR Act).

After 13 years, the Secretary/Lekhpal of Bhumi Prabandhank Samiti, Rampur forwarded a report to the jurisdictional Tehsildar opining thereunder that plot No.185 had been originally designated as Panchayat Ghar and classified under Section 132 of UPZALR Act and accordingly recorded in the revenue records, which had been unlawfully allotted for residential use. The Tehsildar in turn forwarded a proposal to the District Magistrate for cancellation of the allotment which resulted in show cause notices being issued to the writ petitioners and the same was duly replied by them by filing objections.

An application came to be filed by the petitioners to decide the issue of the limitation as preliminary issue, since the proceedings had been initiated after 13 years from the date of allotment contending inter alia that within a period of 3 years the proceedings ought to have been initiated. The Additional Collector opined that there is no limitation fixed under the Act and proceeded to reject the application filed.

The appeal before the Top Court was filed challenging the order of the Allahabad High Court whereunder the writ petition filed by the appellants (writ petitioners) challenging the order passed in Revision came to be dismissed. Consequently the order passed by the Additional Collector holding that proceedings for cancellation of the patta could be started at any time came to be upheld.

The State Counsel submitted that the revenue was empowered under the UPZALR Act to cancel the illegal and fraudulent allotment of land made in favour of the writ petitioners and as such suit had been instituted for cancellation of allotment for which no limitation has been specified under Section 122-C(6) of UPZALR Act and particularly when the land in question had been reserved as Panchayat Ghar it would be governed under Section 132 of the UPZALR Act.

The Division Bench of Justice C.T. Ravikumar & Justice Aravind Kumar noted that the writ petitioners who are rustic and illiterate villagers had submitted applications for allotment of land for purposes of house construction in the village. After the allotment was made, the writ petitioners and other allottees put up construction by putting up residential accommodation and had been residing therein with their family members. However, after a period of 13 years, the Lekhpal submitted a report for cancellation of such allotment.

On the issue of limitation, the Bench referred to the judgment in State of Punjab Vs. Bhatinda Milk Producer Union Limited [LQ/SC/2007/1247] wherein it has been held that if no period of limitation has been prescribed, statutory authority must exercise its jurisdiction within a reasonable period. “In the teeth of the expression any time not being found in sub-section (6) of Section 122-C, it would not detain us for too long to set aside the impugned orders”, the Bench said.

The Bench was of the view that on the basis of presumed irregularities, the Tehsildar had jumped to the conclusion that allotment was irregular, against law and approval of allotment was on the basis of forged signature of Sub- District Magistrate. However, the basis of such a conclusion, namely the signature of the Sub-District Magistrate having been forged, was not specified. Moreover, no allegation of whatsoever nature had been attributed to the allottees of having forged the signatures. In this background, the Bench opined that the principles enunciated by this Court in Ibrahimpatnam Taluk Vyavasaya Coolie Sangham v. K. Suresh Reddy [LQ/SC/2003/797] would be squarely applicable to the facts on hand and as such the order impugned herein couldn’t be sustained.

Further, placing reliance upon Additional Commssioner, Revenue and Others v. Akhalaq Hussain and Another [LQ/SC/2020/318], the Bench said, “We also make it clear that though the power of the Collector is available to initiate suo moto action for cancellation of allotment under sub-section (6) of Section 122-C in case of fraud and such foundational facts would disclose the same, it would suffice to initiate the proceedings as fraud vitiates all proceedings as held in Akhalaq Hussains case referred to supra.”

Another factor which swayed in the Court’s mind to quash the impugned order was the fact that pursuant to the allotment made in 1994 the allottees who are poor rustic villagers had constructed their houses and the allotment was made based on the approval granted by the then Sub-District Magistrate and they had been residing in the residential buildings so constructed by them for the last several years. “...to unsettle the same would result in heaping injustice to those poor hapless persons and particularly when the subject land has been utilized for allotment to the poor and houseless persons”, it held.

Thus, allowing the appeal, the Bench set aside the impugned order as well as the order passed by Additional Collector- respondent No.3 herein and the order of the Additional Commissioner, (Administration) Moradabad Division.

Read Order: Solapur Municipal Corporation v. Shankarrao Govindrao Patil and others Etc [SC- CIVIL APPEAL NOs. 9127-9132 OF 2018]

LE Correspondent

New Delhi, May 21, 2024: Noting the fact that the rights of several workmen are at stake and the issue pertaining to the employment status of workers in the service of Majarewadi Gram Panchayat would turn upon the conclusions that are to be drawn from new documents that have come on record, the Supreme Court has remanded the matter back to the Bombay High Court.

The issue for consideration in these appeals was regarding the status of the respondents herein, viz., the petitioners in the four writ petitions before the High Court, who were engaged in the service of Majarewadi Gram Panchayat, which was merged with Solapur Municipal Corporation (Corporation) along with ten other gram panchayats.

On 25.03.2003, the respondents herein, along with others, were regularized in the service of the Corporation with effect from 01.02.2003. Their claim before the High Court, however, was that they should be treated as having been absorbed in the service of the Corporation from 05.05.1992 itself, in view of the provisions of Section 493(5)(c) of the Bombay Provincial Municipal Corporations Act, 1949. On the other hand, the Corporation contended that they were continued on daily wage basis till 01.02.2003 and, therefore, their employment from 05.05.1992 could not be treated as regular service.

The main issue before the Division Bench of Justice A.S. Bopanna & Justice Sanjay Kumar was regarding the employment status of the respondents herein in the service of Majarewadi Gram Panchayat. The respondents claimed to be the regular employees of the said gram panchayat as on the appointed date, i.e., 05.05.1992. If so, they would be entitled to claim the benefit of Section 493 of the Maharashtra Municipal Corporations Act, 1949 ( Bombay Provincial Municipal Corporations Act, 1949). Section 493 states that the transitory provisions in Appendix IV shall apply to the constitution of the Corporation and other matters specified therein. Clause 5(c) states that all officers and servants in the employ of the said municipality or local authority immediately before the appointed day shall be officers and servants employed by the Corporation under the Act and shall, until other provision is made in accordance with the provisions of the Act, receive salaries and allowances and be subject to the conditions of service to which they were entitled to on such date. The first proviso thereto states that the service rendered by such officers and servants before the appointed day shall be deemed to be service rendered in the service of the Corporation.

The Bench took note of the admitted fact that no material was produced by the respondents before the High Court to establish that they were regular employees of Majarewadi Gram Panchayat before the appointed date. However, a photocopy of Majarewadi Gram Panchayats Resolution No. 83(8) dated 20.03.1992, in Marathi along with an English translation, had been produced. It was stated therein that all the employees working with Majarewadi Gram Panchayat till the end of 31.03.1992 were permanently appointed on regular salary, together with dearness allowance and other allowances. The names of such employees, their designations and their salaries were set out thereafter.

Apart from this document, original orders of appointment in Marathi issued by Majarewadi Gram Panchayat, along with English translations, to some of the respondents had also been produced. The orders of appointment were all dated 20.03.1992. These documents appeared to be genuine, on the face of it, and were duly authenticated by the officials concerned.

The Corporation, on the other hand, would refer to Resolution No.83(9) passed by Majarewadi Gram Panchayat on 20.03.1992, whereby several appointments of seasonal nature were made on a temporary basis. By Resolution No. 83(8), all the employees working with the gram panchayat till 31.03.1992 were permanently appointed whereas Resolution No. 83(9) specifically stated that the 48 temporary appointments made thereunder were to come into effect only on 01.04.1992. Therefore, those 48 appointees were not entitled to claim the benefit of Resolution No. 83(8).

Reference was also made to the Draft Notification reflecting the details of the proposed merger of the gram panchayats with the Corporation, issued by the Government of Maharashtra long before the happening of the events in Majarewadi Gram Panchayat in March, 1992, and it was contended that the entire exercise of the gram panchayat, even if true, was not a bonafide one and that no benefit could be extended to the respondents on the strength thereof.

Considering such aspects, the Bench opined that the the High Court had no occasion to consider it, as the documents in question were produced before the Top Court for the very first time.

“Though, ordinarily, we would not allow documentary evidence to be produced belatedly at the last stage, we are also mindful of the fact that the rights of several workmen are at stake and the issue for consideration would invariably turn upon the conclusions that are to be drawn from these new documents….Such an exercise would be more appropriate before the High Court rather than this Court. Further documentary evidence may have to be led, perhaps, in relation to these new documents and that is not a task that we would normally undertake in exercise of jurisdiction under Article 136 of the Constitution”, the Bench held.

Thus, the Bench observed that the matter would have to be reconsidered by the High Court of Maharashtra at Bombay in the light of and on the strength of the new documents. Allowing the appeals, the Bench restored the writ petitions to the file of the High Court.

The Top Court also held that both parties may be permitted to bring on record such documentary evidence as is deemed fit and necessary by the High Court, for proper reconsideration of the case. The entire matter is now left open for adjudication afresh by the High Court. Given the antiquity of this matter, the Bench has requested the High Court to give it due priority and dispose it of as expeditiously as possible.

Read Order: NATIONAL INVESTIGATION AGENCY NEW DELHI v. OWAIS AMIN @ CHERRY & ORS [SC- CRIMINAL APPEAL NO. 2668 OF 2024]

Tulip Kanth

New Delhi, May 20, 2024: The Supreme Court has clarified that the Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC, 1973) shall be pressed into service from 31.10.2019 onwards in the Union Territory of Jammu & Kashmir. The Top Court partly allowed the appeal of the National Investigation Agency (NIA) in a case where the respondents attempted to ram into a convoy of the CRPF and opined that on the day when the investigation was completed, the Code of Criminal Procedure SVT., 1989 was in force within J&K.

October 31, 2019 is the day on which the Jammu and Kashmir Reorganisation Act came into effect.

Brief facts of the matter at hand are that a case was registered against the respondents under Sections 307, 120-B, 121, 121-A and 124-A of Jammu and Kashmir State Ranbir Penal Code SVT., 1989 (RPC, 1989), Sections 4 and 5 of the Explosive Substances Act, 1908, and Sections 15, 16, 18 and 20 of the UAPA, 1967 by the jurisdictional police.

The said case was re-registered by the appellant subsequent to the order passed by the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA), Government of India. A complaint was conveyed by the District Magistrate, Ramban by way of a communication to the NIA Court in tune with Sections 196 and 196-A of the Code of Criminal Procedure SVT., 1989. Pursuant to the said complaint, investigation was duly completed by the appellant and the respondents were charge-sheeted for the offences under Sections 306, 309, 307, 411, 120-B, 121, 121-A and 122 of RPC, 1989, Sections 16, 18, 20, 23, 38 and 39 of UAPA, 1967, Sections 3 and 4 of Explosive Substances Act, 1908 and Section 4 of the Jammu & Kashmir Public Property (Prevention of Damage) Act, 1985, for making an attempt to ambush and ram the convoy of Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF) personnel by a Santro car laden with explosives. Before their attempt could succeed, a blast occurred resulting in the respondents fleeing from the place of occurrence.

While taking cognizance, the Special Judge, NIA concluded that no cognizance could be taken for the offences charged under Sections 121, 121-A and 122 of the RPC, 1989 as the procedure contemplated under Section 196-B of CrPC, 1989 wasn’t followed. Furthermore, cognizance was also not taken for the offence committed under Section 120-B of RPC, 1989 for the reason that neither was there any authorization, nor was there any empowerment as required under Section 196-A of CrPC, 1989. Resultantly, cognizance was taken for the remaining offences.

Aggrieved by the decision of the Special Judge, NIA, both the appellant and the respondents filed their respective appeals. The Division Bench of the Jammu and Kashmir held that the Special Judge was wrong on two counts, namely, that the complaint made was in accordance with Section 4(1)(e) of CrPC, 1989, and in view of the discretion available under Section 196-B of CrPC, 1989, there was no question of undertaking any mandatory preliminary investigation.

The appellants challenged the judgment rendered by the Division Bench of the Jammu & Kashmir High Court by which the judgment rendered by the Special Judge was confirmed in part, while remitting the issue pertaining to the charges framed under Sections 306 and 411 of the RPC along with Section 39 of the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, 1967 (hereinafter referred to as UAPA, 1967) for taking cognizance afresh.

“There is nothing to infer either from the Act, 2019 or the Order, 2019 that CrPC, 1973 will have a retrospective application. However, the Order, 2019 did take into consideration all the difficulties that might arise by facilitating the continuance thereunder”, the Division Bench of Justice M.M. Surdresh & Justice S.V.N. Bhatti said.

“To make this position clear, the CrPC, 1973 shall be pressed into service from 31.10.2019 onwards, and thus certainly not before the appointed day”, the Top Court held while also adding, “ Thus, any investigation in currency at the time of repealing of any statute, as mentioned in Table 3 of the Fifth Schedule, followed by the introduction of the Act, 2019, shall continue under CrPC, 1989. However, the application of law thereon would be the CrPC, 1973. While so, the CrPC, 1973 cannot be made applicable when the earlier one (i.e. CrPC, 1989) was still in force.”

The Bench was of the opinion that while an investigation could continue after its initiation under the CrPC, 1989, by way of the application of the CrPC, 1973, it couldn’t be stated that even for a case where there was a clear non-compliance of the former, it could be ignored by the application of the latter.

The Top Court explained that Para 2(13) confers sufficient power on the investigating agency to deal with such a situation. “While we are holding that the requirement of an authorization or an empowerment is mandatory for conveying a complaint, it being at the conclusion of investigation, would not preclude the investigating agency from complying with it thereafter. It is an approval from an appropriate authority of the investigation having been completed.”

The Top Court was in complete agreement with the reasoning adopted by the High Court of Calcutta in Nibaran Chandra (supra) as the present was a case where an authority had failed to exercise the said power in granting an authorization.

On the facts of the case, the Bench observed that it was an omission caused by the appellant which needed to be rectified. “It being a curable defect, would not enure to the benefit of the respondents, particularly when they are yet to be charged in the absence of such sanction or empowerment”, the Bench said.

It was reiterated that the complaint was conveyed by the District Magistrate, Ramban to the Special Judge, NIA on 20.09.2019. Further, the investigation was completed with the filing of the chargesheet on 25.09.2019. Whereas, the appointed day for the Act, 2019 was 31.10.2019. Hence, on the day when the investigation stood completed, the CrPC, 1989 was in force within the Union Territory of Jammu & Kashmir.

Thus, the Bench set aside the impugned judgment insofar as it confirmed the judgment of the Special Judge, NIA, in not taking cognizance for the offence punishable under Section 120-B of the RPC, 1989. Accordingly, the Bench gave liberty to the appellant to comply with the mandate of Section 196-A of the CrPC, 1989, by seeking appropriate authorization or empowerment as the case may be. If such a compliance is duly made, then the Trial Court has been asked to undertake the exercise of taking cognizance, and proceed further with the trial in accordance with law.

Read Order: SUNITA DEVI v. THE STATE OF BIHAR & ANR [SC- CRIMINAL APPEAL NO. 3924 OF 2023]

Tulip Kanth

New Delhi, May 20, 2024: While observing that a Judge can never have unrestrictive and unbridled discretion without there being any guidelines in awarding a sentence, the Supreme Court has suggested constitution of an appropriate Committee on sentencing consisting of various experts and stakeholders.

The FIR, in this case, was registered under Section 376AB of the Indian Penal Code, 1860 and Section 4 of the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act, 2012 (POCSO Act, 2012) read with Section 3(2)(v) of the Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989 (SC/ST Act, 1989). for the occurrence that took place in 2021. The case of the prosecution in nutshell was that the accused took advantage of a minor girl child and committed the offence of rape.

The accused was arrested and remanded to judicial custody which was further extended by the orders through video conferencing. The charge-sheet filed was taken on record without the FSL report. The prosecutor was directed to ensure the presence of the accused through video conferencing. On the day when arguments were to be heard on framing of charges were to be framed, the counsel appearing for the accused was provided with the documents, without being given any time and without ensuring that these documents were in fact shown to the accused.

Order for summoning of prosecution witness was passed without without taking into consideration the Witness Protection Scheme, 2018 and the statements of the witnesses were recorded in disregard of the provisions of the Rules for Video Conferencing for Courts, 2020.Thereafter, death sentence was imposed by the trial court. The High Court ordered for a de novo trial. Incidentally, the approach adopted by the Trial Court was found fault with.

Assailing the impugned judgment on merit, both the informant and the Trial Judge filed Criminal Appeals. Another Criminal Appeal was filed by the very same Judge who rendered a similar conviction and sentenced the accused to life imprisonment. The disciplinary proceedings initiated were dropped on the administrative side. However, an application was filed by the Judge alleging that certain administrative work had been taken away from him, apparently on the basis of the impugned judgments, and therefore, he should either be restored with the said power or transferred to some other place.

On a perusal of the impugned judgments, the Division Bench of Justice M.M. Sundresh & Justice S.V.N. Bhatti opined that the High Court, while passing both the impugned judgments, had not only called for the records and rendered findings of fact, but also considered them in detail.

“At every stage, the accused was denied due opportunity to defend himself. The appellant judicial officer was obviously acting in utmost haste. Every trial is a journey towards the truth and a Presiding Officer is expected to create a balanced atmosphere in the mind of the prosecution and the defence. It seems to us that the decision was rendered in utmost haste. It would be humanly impossible to deliver the judgment within half an hours time running into 27 pages consisting of 59 paragraphs in the first case and similarly in the other. The lawyer for the defence cannot fight against the court”, the Bench said.

The Top Court was of the view that at every stage, including framing of charges, there was a constant denial of due opportunity and hearing. The accused was not able to consult his lawyer. He was not even served with the copies, though his lawyer received the same before framing of the charges. Moreover, neither the provisions of the Witness Protection Scheme, 2018 had been invoked nor the Rules for Video Conferencing for Courts, 2020 were followed. The accused was merely shown the court's proceedings and the writing was on the wall for him. On facts, even in the other Criminal Appeal the trial had commenced and concluded in a single day. “When the charges are very serious, Courts should be more circumspect in discharging their solemn duty”, it held while also adding, “The appellant judicial officer is fortunate that no action was taken against him. We do not wish to say anything more on this, except by stating that in the absence of any proposed action, there is no question of hearing the appellant.”

On the application filed seeking intervention over the action taken on the administrative side, the Bench granted liberty to the appellant to approach the High Court on the administrative side. Dismissing the appeal, the Bench directed that the trial court shall keep in mind the mandate of POCSO Act, 2012 while recording the evidence of the victim and complete the trial expeditiously in view of Section 35 of the POCSO Act, 2012.

“The Government of India represented by the Secretary for the Ministry of Law and Justice shall file an affidavit on the feasibility of introducing a comprehensive sentencing policy and a report thereon, within a period of six months from today, as indicated above”, the Bench held while also adding that he Registry shall forward a copy of the judgment to the Department of Justice, Ministry of Law and Justice, Government of India.

Read Order: IN RE: T.N. GODAVARMAN THIRUMULPAD AND ORS v. UNION OF INDIA & ORS [SC- IA NO(S). 2930 OF 2010, 3963 OF 2017, 160714 OF 2019, 77320 OF 2023 AND 79064 OF 2023]

Tulip Kanth

New Delhi, May 20, 2024: While directing the Central Empowered Committee (CEC) or the relevant Competent Authority to adjudicate upon an application seeking permission to construct a health/eco-resort in Hoshangabad District of Madhya Pradesh, the Supreme Court has opined that the applicant is justified in claiming that its proprietary rights guaranteed under Article 300A of the Constitution cannot be infringed merely on account of the pending writ appeal before the Madhya Pradesh High Court.

The interlocutory applications, before the Top Court, had been preferred by the applicant M/s Shewalkar Developers Limited being aggrieved by the inaction of the respondents in deciding the application filed by the applicant seeking permission to construct a health/eco-resort on the subject land situated in District Hoshangabad, Madhya Pradesh. The total area of these two plots is around 59,265 sq. ft. and 49,675 sq. ft., respectively.

The applicant herein approached the Madhya Pradesh High Court by filing Writ Petition seeking a direction to the respondents to favorably consider the prayer of the applicant. The Division Bench permitted the applicant to approach the Central Empowered Committee(CEC). Consequently, the applicant preferred an application to the CEC seeking permission to construct the health/eco-resort on the land mentioned above asserting that the said chunk of land was not a forest land and had been acquired under valid title deeds and thus, the prayer for permission to construct may be allowed. However, the prayer made by the applicant was not accepted whereupon, the applications under consideration came to be filed before the Top Court.

The State Government had previously taken a stand in its counter that the land in issue falls within the limits of Pachmarhi Wildlife Sanctuary and therefore, by virtue of the directions issued by the CEC vide letter dated July 2, 2004, no commercial activity was permissible thereupon, without the permission of the Top Court.

At the outset, the Division Bench of Justice B.R. Gavai & Justice Sandeep Mehta noted that the original application remained pending for almost 14 years. Irrespective of the fact that the order passed by the District Collector purportedly covers the entire area of the Plot, the sale deed executed in favour of the applicant and the mutation made in its name had never been questioned in any Court of law. Neither the Revenue Department nor the State Government authorities took the trouble of impleading the applicant as party in any of the abovementioned litigations.

“The title acquired by the applicant over the subject plots not having been challenged, attained finality and thus the State cannot claim a right thereupon simply because at some point of time, the plots came to be recorded as Nazul lands in the revenue records. The categoric stand in the compliance affidavit filed by the State(reproduced supra) fortifies the claim of the applicant that these plots are falling under the urban area”, the Bench said.

The Bench further held, “In this background, the applicant is justified in claiming that its proprietary rights guaranteed under Article 300A of the Constitution of India cannot be infringed merely on account of the pending writ appeal before the Madhya Pradesh High Court.”

The Top Court was of the firm view that the permission sought by the applicant for raising construction of health/eco- resort cannot be opposed only on account of pendency of the writ appeal before the Madhya Pradesh High Court. A registered sale deed was executed in the year 1991 by the land owner Dennis Torry in favour of the applicant. The Bench observed that activities, if any, on the Plot Nos. 14/3 and 14/4 purchased by the applicant from Dennis Torry would have to be carried out strictly in accordance with the ESZ notification dated 9th August, 2017, issued by the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change. Nonetheless, the applicant would be at liberty to satisfy the authorities that the plots in question are beyond the Eco-Sensitive Zone.

Furthermore, since the writ appeal pending before the Madhya Pradesh High Court arose out of the orders passed in relation to the title rights of Dennis Torry, from whom the applicant purchased the plots in question, the activities, if any, undertaken by the applicant on the said plot of land would also remain subject to the outcome of the said writ appeal.

Thus, the Bench directed that the application filed by the applicant for raising construction on the plot shall be decided objectively by the CEC/Competent Authority of the local body keeping in view the location of the land with reference to the notified boundaries of the ESZ.

While deciding the application filed by the applicant, the authorities have been asked to bear in mind the fact that it is the pertinent case presented before this Court that a large number of resorts of Madhya Pradesh Tourism Development Corporation and Special Area Development Authority(SADA) are existing on areas abutting the land owned by the applicant.The Bench also ordered that applications shall be decided within a period of two months from today.

Read Order: TARSEM LAL v. DIRECTORATE OF ENFORCEMENT JALANDHAR ZONAL OFFICE [SC- CRIMINAL APPEAL NO. 2608 OF 2024]

Tulip Kanth

New Delhi, May 20, 2024: The Supreme Court has clarified that the Directorate of Enforcement (ED) will have to apply to the Special Court in order to seek custody of an accused who appears after service of summons. However, when the ED wants to conduct a further investigation concerning the same offence, it may arrest a person not shown as an accused in the complaint already filed under Section 44(1)(b) of the PMLA provided the requirements of Section 19 are fulfilled.

The appellants, before the Top Court, were the accused persons in complaints under Section 44 (1) (b) of the Prevention of Money Laundering Act, 2002 (PMLA) who were denied the benefit of anticipatory bail by the impugned orders. The facts of the case suggested that they were not arrested after registration of the Enforcement Case Information Report (ECIR) till the Special Court took cognizance under the PMLA of an offence punishable under Section 4 of the PMLA. The cognizance was taken on the complaints filed under Section 44 (1)(b).

The appellants did not appear before the Special Court after summons were served to them. The Special Court issued warrants for procuring their presence. After the warrants were issued, the appellants applied for anticipatory bail before the Special Court but their applications were rejected. Unsuccessful accused preferred these appeals since the High Court had turned down their prayers. The Top Court, by interim orders, had protected the appellants from arrest.

The appellants had contended that the power to arrest vesting in the officers of the Directorate of Enforcement (ED) under Section 19 of the PMLA cannot be exercised after the Special Court takes cognizance of the offence punishable under Section 4 of the PMLA. If an accused appears pursuant to the summons issued by the Special Court, there is no reason to issue a warrant of arrest against him or to take him into custody. It was also submitted that there is nothing inconsistent between Section 88 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 (CrPC) and the provisions of the PMLA.

The respondents, on the other hand, contended that once an accused appears before the Special Court, he is deemed to be in its custody. In view of Section 65, read with Section 71 of the PMLA, the provisions of the PMLA will have an overriding effect over the provisions of the CrPC. It was also submitted that in none of these cases, the conditions incorporated under Section 45 (1) of the PMLA had been fulfilled; therefore, the appellants were disentitled to the grant of anticipatory bail.

The Division Bench of Justice Abhay S. Oka and Justice Ujjal Bhuyan was of the view that if a warrant of arrest has been issued and proceedings under Section 82 and/or 83 of the CrPC have been issued against an accused, he cannot be let off by taking a bond under Section 88. Section 88 is indeed discretionary. But this proposition will not apply to a case where an accused in a case under the PMLA is not arrested by the ED till the filing of the complaint. In such cases, as a rule, a summons must be issued while taking cognizance of a complaint. In such a case, the Special Court may direct the accused to furnish bonds in accordance with Section 88 of the CrPC, it added.

It explained that even if a bond is not furnished under Section 88 by an accused and if the accused remains absent after that, the Court can always issue a warrant under Section 70 (1) of the CrPC for procuring the presence of the accused before the Court. In both contingencies, when the Court issues a warrant, it is only for securing the accused's presence before the Court. When the Special Court deals with an application for cancellation of a warrant, the Special Court is not dealing with an application for bail. Hence, Section 45(1) will have no application to such an application.

The Bench was informed across the Bar by the counsel of the appellants that some of the Special Courts under the PMLA are following the practice of taking the accused into custody after they appear pursuant to the summons issued on the complaint. Therefore, the accused are compelled to apply for bail or for anticipatory bail apprehending arrest upon issuance of summons.

“We cannot countenance a situation where, before the filing of the complaint, the accused is not arrested; after the filing of the complaint, after he appears in compliance with the summons, he is taken into custody and forced to apply for bail. Hence, such a practice, if followed by some Special Courts, is completely illegal. Such a practice may offend the right to liberty guaranteed by Article 21 of the Constitution of India”, it said.

Setting out the required procedure, the Bench said, “If the ED wants custody of the accused who appears after service of summons for conducting further investigation in the same offence, the ED will have to seek custody of the accused by applying to the Special Court. After hearing the accused, the Special Court must pass an order on the application by recording brief reasons. While hearing such an application, the Court may permit custody only if it is satisfied that custodial interrogation at that stage is required, even though the accused was never arrested under Section 19. However, when the ED wants to conduct a further investigation concerning the same offence, it may arrest a person not shown as an accused in the complaint already filed under Section 44(1)(b), provided the requirements of Section 19 are fulfilled.”

In this case, the Bench took note of the fact that warrants were issued to the appellants as they did not appear before the Special Court after the service of summons. The appellants could have applied for cancellation of warrants issued against them as the warrants were issued only to secure their presence before the Special Court. Instead of applying for cancellation of warrants, the appellants applied for anticipatory bail. All of them were not arrested till the filing of the complaint and have co-operated in the investigation.

Therefore, the Bench proposed to direct that the warrants issued against the appellants shall stand cancelled subject to the condition of the appellants giving undertakings to the respective Special Courts to regularly and punctually attend the Special Court on all dates fixed unless specifically exempted by the exercise of powers under Section 205 of the CrPC. Allowing the appeals, the Bench also put forth the condition that the appellants will have to furnish bonds to the Special Court in terms of Section 88 of the CrPC.

Read Order: KOLKATA MUNICIPAL CORPORATION & ANR v. BIMAL KUMAR SHAH & ORS [SC-CIVIL APPEAL NO. 6466 OF 2024]

LE Correspondent

New Delhi, May 20, 2024: The Supreme Court has asserted that the constitutional right to property comprises of seven sub-rights or procedures such as the right to notice, hearing, reasons for the decision, to acquire only for public purpose, fair compensation, efficient conduct of the procedure within timelines and finally the conclusion. The Top Court also dismissed the appeal filed by the Kolkata Municipal Corporation with costs quantified at Rs 5 lakh to be paid to the respondent-land bearer.

The property in question, situated at Narikeldanga in Kolkata belongs to Birinchi Bihari Shah. As Birinchi was minor at the time when his father passed away, his elder brother managed and administered the Property and, in that process, he also let out the premises in favour of one M/s Arora Film Corporation. Upon attaining majority, the Property was mutated in the name of Birinchi Shah.

In the year 2009, when an attempt was made by the appellant-Corporation to forcefully enter and occupy the Property, Birinchi Shah filed a writ petition before the High Court seeking a restraint order against the appellant-Corporation. As there was no real contest about the title in the Property and the appellant-Corporation having not filed any affidavit-in- opposition, the High Court directed that the appellant- Corporation must not make any construction over the Property.

In July 2010, Birinchi Shah received information that the appellant-Corporation had deleted his name from the category of owner and had inserted its own name in the official records. Aggrieved, he approached the High Court. The single Judge restrained the appellant-Corporation from interfering with the possession of Birinchi Shah and also injuncted them from giving effect to the wrongful recording of its name in the official records. Dissatisfied, the appellant-Corporation filed a writ appeal. After the remand, a Writ Petition was filed by the respondent no. 1, the executor to the estate of Birinchi Shah seeking an order quashing the alleged acquisition as illegal and to restore their name as owners in the official records.

The single Judge quashed and set-aside the alleged action of acquisition. The Division Bench directed that the appellant-Corporation may initiate acquisition proceedings for the Property under Section 536 or 537 of the Act, within five months, or in the alternative, restore the name of the last recorded owner as the owner of the Property. It was against this judgment that the appellant-Corporation approached the Top Court.

Rejecting the alternative argument of the appellant-Corporation that there is also a provision for compensation under Section 363 of the Kolkata Municipal Corporation Act, 1980 when land is acquired under Section 352, the Division Bench of Justice Pamidighantam Sri Narasimha and Justice Aravind Kumar examined the constitutional position of acquisition of immovable property whereunder the mere presence of power to acquire coupled with a provision for payment of fair compensation by itself is not sufficient for a valid acquisition.

The Bench opined that the scheme of the Act makes it clear that Section 352 empowers the Municipal Commissioner to identify the land required for the purpose of opening of public street, square, park, etc. and under Section 537, the Municipal Commissioner has to apply to the Government to compulsorily acquire the land. Upon such an application, the Government may, in its own discretion, order proceedings to be taken for acquiring the land. “Section 352 is therefore, not the power of acquisition. We, therefore, reject the submission on behalf of the appellant-Corporation that Section 352 enables the Municipal Commissioner to acquire land”, the Bench said.

Referring to Hindustan Petroleum Corporation Ltd v. Darius Shapur Chenai, [LQ/SC/2005/944] ; K.T. Plantation Pvt Ltd v. State of Karnataka [LQ/SC/2011/1026], the Bench observed that a binary reading of the constitutional right to property must give way to more meaningful renditions, where the larger right to property is seen as comprising intersecting sub-rights, each with a distinct character but interconnected to constitute the whole.

Interpreting authority of law in Article 300A of the Constitution, the Bench held that a minimum content of a constitutional right to property comprises of seven sub-rights or procedures such as the right to notice, hearing, reasons for the decision, to acquire only for public purpose, fair compensation, efficient conduct of the procedure within timelines and finally the conclusion. These sub-rights have synchronously formed part of our laws and have attained judicial recognition. “These seven rights are foundational components of a law that is tune with Article 300A, and the absence of one of these or some of them would render the law susceptible to challenge”, it added.

“Therefore, as Section 352 does not provide for these sub-rights or procedures, it can never be a valid power of acquisition”, the Bench held.

Coming to the facts of the facts of the case where the respondents had taken inconsistent stands about the ownership and acquisition of the Property, the Bench asserted that the exercise of the power is illegal, illegitimate and has caused great difficulty to the respondent-land-bearer. As per the Bench, the High Court was fully justified in coming to the conclusion that the appellant-Corporation acted in blatant violation of statutory provisions. The Bench concurred with the High Court’s decision of allowing the writ petition and rejecting the case of the appellant-Corporation acquiring land under Section 352 of the Act.

Thus, the Top Court dismissed the appeal with costs quantified at Rs.5,00,000 to be paid to respondent no.1 within 60 days.

Read Order: Dharnidhar Mishra (D) and Another v. State of Bihar and Others [SC- Civil Appeal No 6351 of 2024]

LE Correspondent

New Delhi, May 20, 2024: Considering the fact that land acquisition took place in the year 1977 and the State took 42 years to assess the value of the land, the Supreme Court has remitted the matter back to the Patna High Court for fresh consideration. The Top Court also noted that the appellant had passed away and the litigation was now pursued by his legal heirs.

In 1976, a notification under Section 4 of the Land Acquisition Act was issued for the purpose of construction of State Highway as notified by the State of Bihar. The land owned by the appellant herein was included in Section 4 notification and in 1977, the land of the appellant was acquired. However, it was the case of the appellant that not a single penny was paid to him towards compensation.

The appellant preferred an appropriate application addressed to the State Government but the State did not even pass any award of compensation and kept the matter in limbo. Years passed by and the appellant’s issue wasn’t resolved. His writ petition before the Single Judge of the Patna High Court was rejected on the count that the petition was filed after a period of forty-two years of the acquisition.The appeal before the Top Court arose from an order by which the Division Bench disposed of the Letters Patent Appeal by asking the appellant to file an appropriate application before the concerned authority for disbursement of the value of the land assessed at Rs 4,68,099.

The State Counsel submitted that it was not in dispute that the land of the appellant was acquired for a public purpose, but at the same time, it was the duty of the appellant to pursue the matter further for the purpose of getting appropriate compensation determined in accordance with law.

Noting that the High Court in its impugned order had stated that the appellant herein had been informed about the value of the land assessed at Rs 4,68,099, the Division Bench of Justice J.B. Pardiwala & Justice Manoj Misra failed to understand the basis on which this figure was arrived at; at what point of time this amount came to be assessed; and the basis for the assessment of such amount. The Bench opined that the order of the High Court could be said to be a non-speaking order and there was nothing to indicate that any consent was given by the appellant herein to pass such an order.

“The first thing that the High Court should have enquired with the State is as to why in the year 1977 itself, that is the year in which the land came to be acquired, the award for compensation was not passed. The High Court should have enquired why it took forty-two years for the State to determine the figure of Rs 4,68,099”, the Bench said while further adding, “We are not convinced but rather disappointed with the approach of the High Court while disposing of the appeal.”

The Bench also remarked, “It is sad to note that the appellant passed away fighting for his right to receive compensation. Now the legal heirs of the appellant are pursuing this litigation.”

It was further explained that in 1976, when the land of the appellant came to be acquired, the right to property was a fundamental right guaranteed by Article 31 in Part III of the Constitution. Article 31 guaranteed the right to private property, which could not be deprived without due process of law and upon just and fair compensation.

The right to property ceased to be a fundamental right by the Constitution (Forty-Fourth Amendment) Act, 1978, however, it continued to be a human right in a welfare State, and a constitutional right under Article 300-A of the Constitution. Article 300-A provides that no person shall be deprived of his property save by authority of law. The State cannot dispossess a citizen of his property except in accordance with the procedure established by law, the Bench asserted.

Referring to the judgments in Hindustan Petroleum Corpn. Ltd. v. Darius Shapur Chenai reported in (2005) 7 SCC 627 [LQ/SC/2005/944] ; N. Padmamma v. S. Ramakrishna Reddy [LQ/SC/2008/1259]; Delhi Airtech Services (P) Ltd. v. State of U.P. [LQ/SC/2011/1087] , the Bench highlighted right to property being a basic human right. It said, “We regret to state that the learned Single Judge of the High Court did not deem fit even to enquire with the State whether just and fair compensation was paid to the appellant or not. The learned Single Judge rejected the writ petition only on the ground of delay.”

Thus, allowing the appeal, the Bench set aside the impugned order passed by the High Court and remitted the matter for fresh consideration.

Read Order: MR. R.S. MADIREDDY AND ANR. ETC v. UNION OF INDIA & ORS. ETC [SC- CIVIL APPEAL NO (S). 6473-6476 OF 2024]

Tulip Kanth

New Delhi, May 20, 2024: The Supreme Court has asserted that no writ petition is maintainable against Air India Limited as the erstwhile Government run airline, having been taken over by a private company, is not performing any public duty anymore. However, the Apex Court has granted liberty to the former cabin crew members to approach the appropriate forum for raising their service-related issues.

The appeals, before the Top Court, were filed challenging the common impugned judgment of the Division Bench of the Bombay High Court dismissing four writ petitions instituted by the appellants being the former employees of respondent No.3 i.e. Air India Limited( AIL) as members of its cabin crew force. Appellants came to be employed in AIL in the late 1980s and all of them retired between 2016 and 2018.

Air India was a statutory body constituted under the Air Corporations Act, 1953. With the repeal of the Act of 1953, Air India merged with Indian Airlines and upon incorporation, respondent No. 3(AIL) became a wholly Government owned company and, thus, came under the category of other authorities within the meaning of Article 12 of the Constitution of India. This status of Air India continued to subsist on the date when the subject batch of writ petitions under Article 226 of the Constitution of India were filed before the High Court invoking writ jurisdiction, against respondent No.3(AIL).

However, in 2021, pursuant to the share purchase agreement signed with Talace India Pvt. Ltd., 100% equity shares of the Government of India in respondent No. 3(AIL) were purchased by the said private company and respondent No. 3(AIL) was privatised and disinvested. Therefore, the writ petitions were maintainable on the date of institution but the question that arose before the High Court was whether they continued to be maintainable as on the date the same were finally heard.

The Division Bench of the High Court concluded that with the privatization of respondent No. 3(AIL), jurisdiction of the High Court under Article 226 of the Constitution of India to issue a writ to respondent No. 3(AIL), particularly in its role as an employer, did not subsist and disposed of the writ petitions vide common impugned judgment which was assailed before the Apex Court in the present appeals by special leave.

It was the case of the appellants that the writ petitions were filed with genuine and bona fide service-related issues of the appellant employees based on substantive allegations of infringement of fundamental rights guaranteed under Article 14 and Article 16 of the Constitution of India.

Reiterating that a writ cannot be issued against non-state entities that are not performing any Public Function, the Counsel for the respondent pointed out that it was the conceded case of the appellants that post privatisation, respondent No. 3(AIL) does not perform any Public Function and in any case running a private airline with purely a commercial motive can never be equated to performing a Public Duty.

The Division Bench of Justice B.R. Gavai and Justice Sandeep Mehta took note of the fact that the Government of India having transferred its 100% share to the company Talace India Pvt Ltd., ceased to have any administrative control or deep pervasive control over the private entity and hence, the company after its disinvestment could not have been treated to be a State anymore after having taken over by the private company. Thus, the respondent No.3(AIL) after its disinvestment ceased to be a State or its instrumentality within the meaning of Article 12 of the Constitution of India.

Reliance was also placed upon the judgements in Federal Bank Ltd. v. Sagar Thomas [LQ/SC/2003/993] and Pradeep Kumar Biswas v. Indian Institute of Chemical Biology [LQ/SC/2002/499]. “Once the respondent No.3(AIL) ceased to be covered by the definition of State within the meaning of Article 12 of the Constitution of India, it could not have been subjected to writ jurisdiction under Article 226 of the Constitution of India”, it added.

The Bench further opined that respondent No.3(AIL), the erstwhile Government run airline having been taken over by the private company Talace India Pvt. Ltd., unquestionably, is not performing any public duty inasmuch as it has taken over the Government company Air India Limited for the purpose of commercial operations. Thus, the Bench held that no writ petition is maintainable against respondent No.3(AIL).

The respondent No.3(AIL)- employer was a government entity on the date of filing of the writ petitions, which came to be decided after a significant delay by which time, the company had been disinvested and taken over by a private player. Since, AIL had been disinvested and had assumed the character of a private entity not performing any public function, the High Court could not have exercised the extra ordinary writ jurisdiction to issue a writ to such private entity. The Division Bench had taken care to protect the rights of the appellants to seek remedy and thus, it couldn’t be said that the appellants had been non-suited in the case. As per the Bench, the appellants would have to approach another forum for seeking their remedy.

“By no stretch of imagination, the delay in disposal of the writ petitions could have been a ground to continue with and maintain the writ petitions because the forum that is the High Court where the writ petitions were instituted could not have issued a writ to the private respondent which had changed hands in the intervening period”, the Bench held.

The Top Court affirmed the view taken by the Division Bench of the High Court in denying equitable relief to the appellants herein and relegating them to approach the appropriate forum for ventilating their grievances. Noting that the appellants raised grievances by way of filing the captioned writ petitions between 2011 and 2013 regarding various service-related issues which cropped up between the appellants and the erstwhile employer between 2007 and 2010, the Bench opined that the writ petitions came to be instituted with substantial delay from the time when the cause of action had accrued to the appellants.

Thus, dismissing the appeals, the Bench held, “In wake of the discussion made hereinabove, we do not find any reason to take a different view from the one taken by the Division Bench of the Bombay High Court in sustaining the preliminary objection qua maintainability of the writ petitions preferred by the appellants and rejecting the same as being not maintainable.”

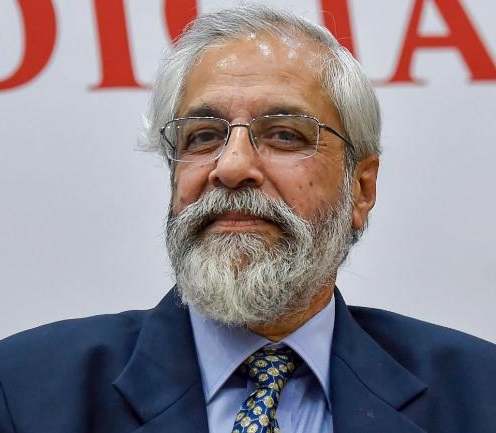

Time for judiciary to introspect and see what can be done to restore people’s faith – Justice Lokur

Justice Madan B Lokur, was a Supreme Court judge from June 2012 to December 2018. He is now a judge of the non-resident panel of the Supreme Court of Fiji. He spoke to LegitQuest on January 25, 2020.

Q: You were a Supreme Court judge for more than 6 years. Do SC judges have their own ups and downs, in the sense that do you have any frustrations about cases, things not working out, the kind of issues that come to you?

A: There are no ups and downs in that sense but sometimes you do get a little upset at the pace of justice delivery. I felt that there were occasions when justice could have been delivered much faster, a case could have been decided much faster than it actually was. (When there is) resistance in that regard normally from the state, from the establishment, then you kind of feel what’s happening, what can I do about it.

Q: So you have had the feeling that the establishment is trying to interfere in the matters?

A: No, not interfering in matters but not giving the necessary importance to some cases. So if something has to be done in four weeks, for example if reply has to be filed within four weeks and they don’t file it in four weeks just because they feel that it doesn’t matter, and it’s ok if we file it within six weeks how does it make a difference. But it does make a difference.

Q: Do you think this attitude is merely a lax attitude or is it an infrastructure related problem?

A: I don’t know. Sometimes on some issues the government or the establishment takes it easy. They don’t realise the urgency. So that’s one. Sometimes there are systemic issues, for example, you may have a case that takes much longer than anticipated and therefore you can’t take up some other case. Then that necessarily has to be adjourned. So these things have to be planned very carefully.

Q: Are there any cases that you have special memories of in terms of your personal experiences while dealing with the case? It might have moved you or it may have made you feel that this case is really important though it may not be considered important by the government or may have escaped the media glare?

A: All the cases that I did with regard to social justice, cases which concern social justice and which concern the environment, I think all of them were important. They gave me some satisfaction, some frustration also, in the sense of time, but I would certainly remember all these cases.

Q: Even though you were at the Supreme Court as a jurist, were there any learning experiences for you that may have surprised you?

A: There were learning experiences, yes. And plenty of them. Every case is a learning experience because you tend to look at the same case with two different perspectives. So every case is a great learning experience. You know how society functions, how the state functions, what is going on in the minds of the people, what is it that has prompted them to come the court. There is a great learning, not only in terms of people and institutions but also in terms of law.

Q: You are a Judge of the Supreme Court of Fiji, though a Non-Resident Judge. How different is it in comparison to being a Judge in India?

A: There are some procedural distinctions. For example, there is a great reliance in Fiji on written submissions and for the oral submissions they give 45 minutes to a side. So the case is over within 1 1/2 hours maximum. That’s not the situation here in India. The number of cases in Fiji are very few. Yes, it’s a small country, with a small number of cases. Cases are very few so it’s only when they have an adequate number of cases that they will have a session and as far as I am aware they do not have more than two or three sessions in a year and the session lasts for maybe about three weeks. So it’s not that the court sits every day or that I have to shift to Fiji. When it is necessary and there are a good number of cases then they will have a session, unlike here. It is then that I am required to go to Fiji for three weeks. The other difference is that in every case that comes to the (Fiji) Supreme Court, even if special leave is not granted, you have to give a detailed judgement which is not the practice here.

Q: There is a lot of backlog in the lower courts in India which creates a problem for the justice delivery system. One reason is definitely shortage of judges. What are the other reasons as to why there is so much backlog of cases in the trial courts?

A: I think case management is absolutely necessary and unless we introduce case management and alternative methods of dispute resolution, we will not be able to solve the problem. I will give you a very recent example about the Muzaffarpur children’s home case (in Bihar) where about 34 girls were systematically raped. There were about 17 or 18 accused persons but the entire trial finished within six months. Now that was only because of the management and the efforts of the trial judge and I think that needs to be studied how he could do it. If he could do such a complex case with so many eyewitnesses and so many accused persons in a short frame of time, I don’t see why other cases cannot be decided within a specified time frame. That’s case management. The second thing is so far as other methods of disposal of cases are concerned, we have had a very good experience in trial courts in Delhi where more than one lakh cases have been disposed of through mediation. So, mediation must be encouraged at the trial level because if you can dispose so many cases you can reduce the workload. For criminal cases, you have Plea Bargaining that has been introduced in 2009 but not put into practice. We did make an attempt in the Tis Hazari Courts. It worked to some extent but after that it fell into disuse. So, plea bargaining can take care of a lot of cases. And there will be certain categories of cases which we need to look at carefully. For example, you have cases of compoundable offences, you have cases where fine is the punishment and not necessarily imprisonment, or maybe it’s imprisonment say one month or two month’s imprisonment. Do we need to actually go through a regular trial for these kind of cases? Can they not be resolved or adjudicated through Plea Bargaining? This will help the system, it will help in Prison Reforms, (prevent) overcrowding in prisons. So there are a lot of avenues available for reducing the backlog. But I think an effort has to be made to resolve all that.

Q: Do you think there are any systemic flaws in the country’s justice system, or the way trial courts work?

A: I don’t think there are any major systemic flaws. It’s just that case management has not been given importance. If case management is given importance, then whatever systematic flaws are existing, they will certainly come down.

Q; And what about technology. Do you think technology can play a role in improving the functioning of the justice delivery system?

I think technology is very important. You are aware of the e-courts project. Now I have been told by many judges and many judicial academies that the e-courts project has brought about sort of a revolution in the trial courts. There is a lot of information that is available for the litigants, judges, lawyers and researchers and if it is put to optimum use or even semi optimum use, it can make a huge difference. Today there are many judges who are using technology and particularly the benefits of the e-courts project is an adjunct to their work. Some studies on how technology can be used or the e-courts project can be used to improve the system will make a huge difference.

Q: What kind of technology would you recommend that courts should have?

A: The work that was assigned to the e-committee I think has been taken care of, if not fully, then largely to the maximum possible extent. Now having done the work you have to try and take advantage of the work that’s been done, find out all the flaws and see how you can rectify it or remove those flaws. For example, we came across a case where 94 adjournments were given in a criminal case. Now why were 94 adjournments given? Somebody needs to study that, so that information is available. And unless you process that information, things will just continue, you will just be collecting information. So as far as I am concerned, the task of collecting information is over. We now need to improve information collection and process available information and that is something I think should be done.

Q: There is a debate going on about the rights of death row convicts. CJI Justice Bobde recently objected to death row convicts filing lot of petitions, making use of every legal remedy available to them. He said the rights of the victim should be given more importance over the rights of the accused. But a lot of legal experts have said that these remedies are available to correct the anomalies, if any, in the justice delivery. Even the Centre has urged the court to adopt a more victim-centric approach. What is your opinion on that?

You see so far as procedures are concerned, when a person knows that s/he is going to die in a few days or a few months, s/he will do everything possible to live. Now you can’t tell a person who has got terminal cancer that there is no point in undergoing chemotherapy because you are going to die anyway. A person is going to fight for her/his life to the maximum extent. So if a person is on death row s/he will do everything possible to survive. You have very exceptional people like Bhagat Singh who are ready to face (the gallows) but that’s why they are exceptional. So an ordinary person will do everything possible (to survive). So if the law permits them to do all this, they will do it.

Q: Do you think law should permit this to death row convicts?

A: That is for the Parliament to decide. The law is there, the Constitution is there. Now if the Parliament chooses not to enact a law which takes into consideration the rights of the victims and the people who are on death row, what can anyone do? You can’t tell a person on death row that listen, if you don’t file a review petition within one week, I will hang you. If you do not file a curative petition within three days, then I will hang you. You also have to look at the frame of mind of a person facing death. Victims certainly, but also the convict.

Q: From the point of jurisprudence, do you think death row convicts’ rights are essential? Or can their rights be done away with?

A: I don’t know you can take away the right of a person fighting for his life but you have to strike a balance somewhere. To say that you must file a review or curative or mercy petition in one week, it’s very difficult. You tell somebody else who is not on a death row that you can file a review petition within 30 days but a person who is on death row you tell him that I will give you only one week, it doesn’t make any sense to me. In fact it should probably be the other way round.

Q: What about capital punishment as a means of punishment itself?